Nurses cared for the casualties of the First World War in Europe (on the Western and Eastern Fronts and in the Eastern Mediterranean), in the Middle East (Egypt & Palestine) and in Mesopotamia, India and Africa.

Nursing work overlapped significantly with that of the physician and surgeon ….A nurse who made a seriously ill and perhaps physically helpless patient comfortable in a clean bed, dressed his wounds, eased his pain and distress, assisted him with his washing and ensured that he had an adequate intake of food and fluids, was practising outside, and well beyond, the domain of medicine, performing skilled tasks essential to the maintenance or restoration of health. They not only kept the patient in the best possible physical health but kept him emotionally and psychologically well, further enhancing the physical healing.

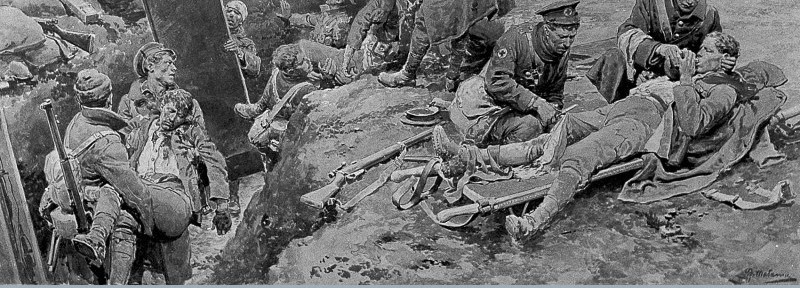

In Western Europe, many nurses worked in casualty clearing stations and field hospitals close to the front line and often received the battle wounded within a few hours of injury and it was their job to sustain life. They dealt with shock caused by injury, haemorrhage, pain and exposure to cold.

When a combatant was wounded on the Western Front his first encounter with the Army Medical Services was usually with his unit’s stretcher bearers. Upon reaching the relative safety of his own lines, he would be taken to his regimental first-aid post and then conveyed to a casualty clearing station….The first assessment of the wounded was performed by medical officers and by trained nursing staff, and was essential to survival …Decisions were taken on which cases were the most urgent; these would be operated on immediately. Others were maintained in as stable a condition as possible while they waited their turn.

As directed nurses administered stimulants, oxygen and morphine. Experienced nurses extracted shrapnel, dirt and other foreign bodies from wounds which were then dressed and repeatedly re-dressed. Nurses dealt with gas gangrene, haemorrhage, fractures, tetanus, trench foot and the aftermath of gas attacks. They assisted at operations and carried out minor surgical procedures when the surgical team were under pressure. Hygiene and infection control were given high priority with the help of iodine, carbolic acid and hydrogen peroxide.

The stress placed on the nurses when they were unable to save a patient, or when overwhelmed with the number of wounded in the aftermath of battle resonates through their diaries and letters. The personal writings of these nurses suggest that their outward display of impassivity belied their feelings of distress.

Working close enough to the battle line to be able to assist the injured in the acute phase, within the first few hours of injury, also meant much physical hardship. At times there were no floors in the marquees owing to shortage of duck boards; the ground was saturated and the nursing staff waded about in mud. They coped with limited supplies of food and drinking water, vermin such as lice, limited lighting and laundry facilities and extreme weather conditions. In countries further afield they had to cope with malaria, dysentery, typhoid and other enteric diseases, cholera, hot arid climates, extreme winter cold and frostbite, dust, flies, mosquitoes…..

Large numbers of nurses sustained serious illness and some died on active service and suffered from infection, overwork and stress. They came under shell fire, were on ships that were torpedoed and nursed patients with dangerous infections. They put their own lives at risk and many were killed or seriously injured during their wartime service.

WW1 Nurses were a link to home; they wrote letters on behalf of their patients, or communicated with bereaved relatives. Once the battle for a patient’s survival had been won, the nurse turned her attention to his long term recovery and rehabilitation.

Material extracted from: ‘Containing Trauma: Nursing Work in the First World War’ by Christine E Hallett published by the Manchester University Press 2009.

On 6 August, 1914, two days after the British Government declared war on Germany, Kate Luard joined the Reserve of Queen Alexandra’s Imperial Military Nursing Service and was to serve on the Western Front until December 1918.

Ambulance trains

For most of the first year of the war, 1914-1915, Kate worked on ambulance trains in France. These trains transported the wounded from casualty clearing stations to Base Hospitals at one of the Channel ports. In 1914 some of the trains in which the wounded travelled were old French trucks where they lay on straw; others were French passenger trains which were being converted by the British to ambulance trains. Later the trains were fitted out as mobile hospitals with operating theatres, bunk beds, kitchens etc and were staffed by a full complement of QAIMNS nurses, RAMC doctors & surgeons, and orderlies.

Casualty Clearing Stations (CCSs)

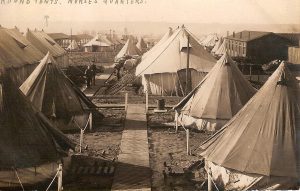

These were part of the casualty evacuation chain, after the regimental aid posts and field dressing stations, which were generally located near rail lines and waterways so that the wounded could be evacuated easily to base hospitals. A CCS often had to move at short notice as the front line changed. Although some were situated in permanent buildings, many consisted of large areas of tents and marquees. Facilities included medical and surgical wards, operating theatres, dispensary, kitchens, sanitation, medical stores, incineration plant, mortuary, ablution and sleeping accommodation. Several CCSs were usually located near each other to enable flexibility.

From 1915-1918 Kate was posted to a number of CCSs, including as Head Sister to Number 32 which specialised in abdominal wounds; and which became one of the most dangerous when the unit was relocated, in late July 1917, to Brandhoek to serve the push that was to become the Battle of Passchendaele, and where she had a staff of 40 nurses and nearly 100 orderlies.

Tented Nurses’ Quarters at a Casualty Clearing Station

Good to see that there are still informative blogs out here, thanks.