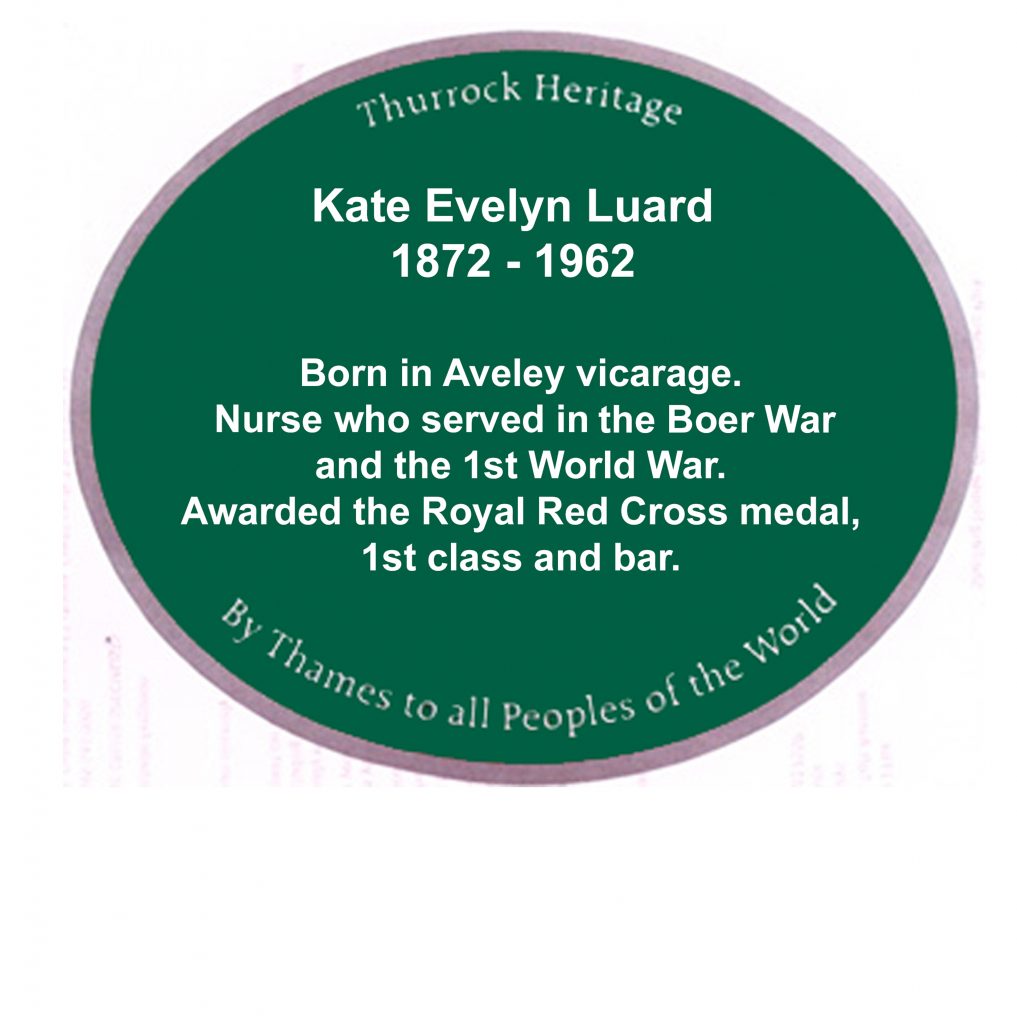

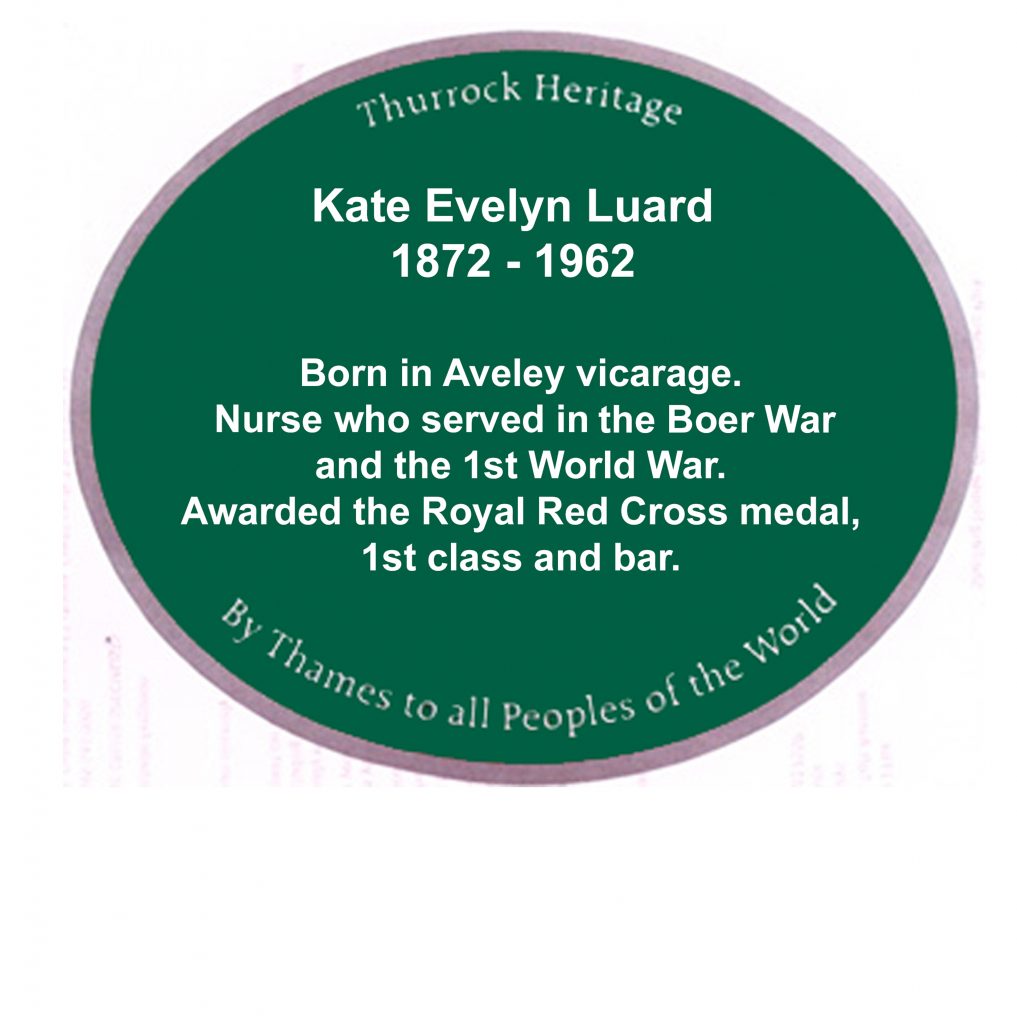

In November 2019 a lottery funded Heritage plaque in honour of Kate Evelyn Luard was unveiled in St. Michael’s Church, Aveley. (Aveley Vicarage where she was born no longer exists).

The plaque now erected on the church wall

In November 2019 a lottery funded Heritage plaque in honour of Kate Evelyn Luard was unveiled in St. Michael’s Church, Aveley. (Aveley Vicarage where she was born no longer exists).

This specialist unit was opened at Basildon University Hospital, Essex, in May 2016. With eight beds and an assessment area this was then to the care of short stay elderly and frail patients, working closely with community healthcare

This is now a specialist ward dedicated to trauma and orthopaedic patients of a range of ages; a criteria lead discharge unit involving a multidisciplinary team.

Amidst the horrors of the Great War and the often insurmountable pressure of nursing the wounded soldiers Kate found time to note not only the extremes of weather but the landscape and flora. This love of nature must have lifted her spirits during these stressful times.

Diary of a Nursing Sister on the Western Front 1914-1915 (ambulance trains)

Tuesday, November 17th, 1914, 7 a.m. Lovely sunrise over winter woods and frosted country. Our load is a heavy and anxious one – 344; we shall be glad to land them safely somewhere. The amputations, fractures and lung cases stand these long journeys very badly.

Wednesday, 18th November, 5 p.m. This long journey from Belgium down to Havre has been a strange mixture. Glorious country with the flame and blue haze of late autumn on hills, towns, and valleys, bare beech-woods with hot red carpets. Glorious British Army lying broken on the train …

Tuesday, 26th January, 1915. A dazzling blue spring day. As we were not going to load at Rouen till 3 p.m., we went for the most glorious walk. We crossed the ferry over the Seine to the foot of the steep high line of hills which eventually looks over Rouen, and climbed up to the top by a lovely winding woody path in the sun and then took a tram down a very steep track into Rouen. I was standing in the front of the tram for the view over Rouen, which was dazzling, with the spires and the river and the bridges.

Wednesday, February 3rd. Moved on last night, and woke up at Bailleul. Some badly wounded on the train. Beyond Rouen, the honeysuckle is in leaf, the catkins are out, and the woods are full of buds. What a difference it will make when spring comes.

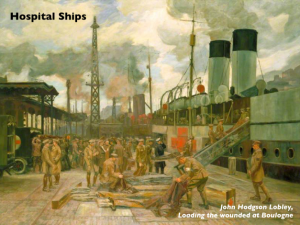

Friday, February 5th, Boulogne. Today has been a record day of brilliant sun, blue sky and warm air, and it has transformed the muddy, sloppy, dingy Boulogne of the last two months into something more like Cornwall. We went in the town in the morning and on the long stone pier in the afternoon. On the pier there were gulls, and a sunny sort of salt wind and big waves breaking, and a glorious view of the steep little town piled up in layers above the harbour, which is packed with shipping.

Sunday, February 7th, Blendecque. We went for a splendid walk this morning uphill to a pine wood bordered by a moor with whins [gorse]. I’ve now got in my bunky hole on the train (it is not quite six feet square) a polypod fern, a plate of moss, a pot of white hyacinths, and also catkins, violets and mimosa!

Wednesday, March 10th. We got to Étretat at about 3 p.m. yesterday after a two days and one night load. The sea was a thundery blue, and the cliffs lit up yellow by the sun, and with the grey shingle it made a glorious picture to take back to the train. It had been a heavy journey with badly wounded.

We are now full of convalescents for Havre to go straight on the boat. There are crowds of primroses out on the banks. Our infant R.A.M.C. cook has just jumped off the train while it was going, grabbed a handful of primroses, and leapt on the train again some coaches back. He came back panting and rosy, and, said, “I’ve got something for you, Sister!” I got some Lent lilies in Rouen, and have some celandines growing in moss, so it looks like spring in my bunk.

Thursday, March 11th. We are being rushed up again without being stopped at Rouen. The birds are singing like anything now, and all the buds are coming out, and the banks and woods are a mass of primroses.

Tuesday, March 23rd, midnight. Have seen cowslips and violets on wayside. Train running very smoothly.

(Kate is posted to No.4 Field Ambulance at Festubert on 2nd April – which she calls “Life at the back of the Front” and has no time to observe landscapes or flora.)

Unknown Warriors: the Letters of Kate Luard, RRC and Bar, Nursing Sister in France 1914-1918. (Casualty Clearing Stations)

Tuesday, April 11th, Lillers. 1916. We had all the acute surgicals out in their beds in the sun to-day in the school yard, round the one precious flower-bed, where are wallflowers and pansies. We went for a walk after tea in the woods, found violets, cowslips and anemones.

Wednesday, April 19th. Orders came yesterday for us to take in no more patients and stand by to move.

Tuesday, May 16th, Barlin. Sister S. and I had another ten-mile ramble to-day. It was again a blue day and the forest was lovely beyond words, full of purple orchis and delicate green and the songs of little birds, and ferns. We tracked up through it over the ridge and down the other side looking over Vimy with a spreading view of a peaceful kind.. We had our tea under some pines …

Saturday, March 17th.1917…. and no sign of any buds out anywhere in these parts. I’ve got a plate of moss with a celandine plant in the middle, and a few sprouting twigs of honeysuckle that you generally find in January, and also a bluebell bulb in a jam tin.

Saturday, April 21st. No rain for once, and the swamp drying up. Went for a walk and found periwinkles, paigles, anemones and a few violets – not a leaf to be seen anywhere.

Monday, April 30th. We have had a whole week without snow or rain – lots of sun and blue sky. I went for a ramble after tea yesterday to a darling narrow wood with a stream. Two sets of shy, polite boys thrust their bunches of cowslips and daffodils into my hand. Also banks of small periwinkles like ours, and flowering palm; absolutely no leaves anywhere and it’s May Day to-morrow.

Wednesday, May 9th. And what do you think we have been busy over this morning? A large and festive Picnic in the woods, far removed from gas gangrene and amputations. We had an ambulance and two batmen to bring the tea in urns to my chosen spot – on the slope of the wood, above the babbling brook, literally carpeted with periwinkles, oxlips and anemones. We had a bowl of brilliant blue periwinkles in the middle of the table.

Monday, May 14th. … it was Gommécourt over again but in newly sprung green this time. I think it made the hilly, curly orchards and wooded villages look sadder than ever, to see the blossom among the ruins, and the mangled woods struggling to put their green clothes on to their distorted spikes.

Friday, May 25th. Dazzling weather and very little doing. The woods are full of bluebells and bugloss and stitchwort, and the fields of buttercups and sorrel.

Friday, June 1st. We are rather full just now. There are fields between woods, snowy with the hugest oxeye daises I ever met, like a field in the Alps in June. Early mornings – high-noons – evenings – nights: all are prefect – we haven’t had one death for nearly a week.

Saturday, August 18th. We’ve had two dazzling days, but as there is not a blade of grass or a leaf in the Camp, only duckboards, trenches and tents, you can only feel it’s summer by the sky and air.

Monday, March 4th, 1918. I’ve got some primroses growing in a blue pot, grubbed up out of a ruined garden in infancy before the snow, now blooming like the Spring. The only way of getting into my Armstrong Hut at first was across a plank over a shell hole. The Royal Engineers are fortifying our quarters against bombs.

Friday, April 12th, Nampes. Orders came for me on Wednesday to take over the C.C.S. in Nampes. Two other sisters came too, and we took the road by car after tea, arriving here at 11 p.m., after losing the way in the dark and attempting lanes deep in unfathomable sloughs of mud. It is an absolutely divine spot, on the side of a lovely wooded valley, south of Amiens. The village is on a winding road, with a heavenly view of hills and woods, which are carpeted with blue violets and periwinkles and cowslips, and starry with anemones. Birds are carolling and leaves are greening, and there is the sun and sky of summer. The blue of the French troops in the fields and roads adds to the dazzling picture, and inside the tents are rows of ‘multiples’ and abdominals, and heads and moribunds, and teams working all night in the Theatre, to the sound of frequent terrific bombardments.

Tuesday, June 4th, 10.30 p.m. The weather continues unnaturally radiant. There is always a breeze waving over the cornfields and the hills are covered with woods near the valleys, with open downs at the top. Below are streams through shady orchards and rustling poplars – and you can see for miles from the downs.

Sunday, June 16th. We emerge about 7.30 from our dug-outs, to a loud continuous chorus of larks, and also to the hum and buzz of whole squadrons of aeroplanes, keeping marvellous V formations against a dazzling blue and white of the sky. The hills are covered with waving corn, like watered silk in the wind, with deep crimson clover, and fields of huge oxeye daisies, like moving sheets. To-day there is no sound of guns and it is all Peace and loveliness.

Wednesday, August 7th, 11.15 p.m. All is ready for Berlin. I’m hoping breathlessly that they hold back my leave to see this through.

Katherine Evelyn Luard, whose diary of 1914-1915 was published during the war, was an experienced and indefatigable nurse, one of the few English nurses who managed to get herself near the front with the RAMC during the war’s first autumn. This was due no doubt to her skill and her apparent imperturbability. Her diary combines the immediacy of the best letters and diaries with the insightful observation and consistently calm and hopeful tone of the few good early-war “reports” (it is tempting, if a little facile, to see the personality of the valued nurse in the valuable writer), and is one of the best sources for the war’s first few months. She travels all over northern France with the ambulance trains that evacuate the wounded, recording the polite thanks and the agony of wounded and dying soldiers from France, Germany, England, Scotland, Ireland, Wales, and India. She also provides a good sense of the nurse’s life–she reports on when she can sneak in exercise or grab a bath, and she is assiduous about visiting all of the Gothic churches–but as the diary goes on she seems to become more and more invested in speaking for the broken bodies which she cares for. She is among the first of the writers here to write repeatedly of her horror at the suffering of all the war’s victims–British and German, soldier and non-combatant. Her later letters, recently republished as Unknown Warriors: The Letters of Kate Luard, continue the story, and solidify her place as one of the most consistently perceptive and interesting writers from “just behind” the lines.

BATTLEFIELD GUIDE to the Ypres Salient and Passchendaele 2017

Major & Mrs Holt

CCS 32 was one of those set up and managed by Head Sister, Kate Luard, RRC & Bar. This most extraordinary woman – capable and efficient, compassionate, determined, brave, totally au fait with, and knowledgeable about, the military situation at all times, had served in the Boer War and went on to use her experience in most key battle areas of WW1. Her brilliant, informative letters to her family are reproduced in Unknown Warriors. It really is essential reading to understand the work of the brilliant medical teams who worked under the most appalling conditions to do all possible for the welfare of their patients, and of the stoicism and humour of the most terribly wounded men.

The Brandhoek CCSs were revolutionary in that they were nearer to the front line than previous CCSs and therefore could offer immediate treatment to the wounded. This concept was the brainchild of another exceptional Medical Officer, Sir Anthony Bowlby, who worked closely with Head Sister Luard as the CCSs came under direct fire by bomb and shell.

This should get this remarkable woman’s achievements to several thousand interested readers…

Valmai Holt

BASILDON UNIVERSITY HOPSITAL, ESSEX

The Kate Evelyn Luard Unit was officially opened in May 2016 at Basildon University Hospital, Essex: a new ward with eight beds and assessment area providing care for older patients who require a short stay in hospital.

Members of Kate Evelyn Luard’s family, Caroline Stevens (great-niece) and Tim Luard (great-nephew) cut the ribbon. Tim Luard said “Our family is very proud to be here today to see the opening of the Kate Evelyn Luard Unit. She was a brave lady who nursed with compassion and humour. She would have been thrilled to bits.

NATIONAL RAILWAY MUSEUM, YORK

A new WW1 exhibition Ambulance Trains was launched in July 2016 in which Kate Evelyn Luard featured prominently.

Unknown Warriors twitter 11 November 2018

‘Lest we forget the powerful words of Kate Luard, WW1 nurse whose voice brought home the visceral force of life at the front and relentless assault on the senses that had to be endured. Soldiers were shell shocked but what of the nurses?’

Letter of 18 December 2014

I found ‘Unknown Warriors’ a powerful and engrossing book and it left me utterly humbled at the hardships which the medical teams suffered in World War One, and impressed at the lengths they would go if there was any hope at all of saving life or limb. The successes which they had must have been indeed uplifting.

TOC H JOURNAL

Vol.V111 July, 1930 No.7

Very little has ever been said or written about the devoted band of women—a handful of them Foundation Members in their own right—who were the first nurses a wounded man encountered as he came out of the Ypres Salient. Many a man is alive to day because of their ministry, and Talbot House received them, as its only women visitors, with special welcome on their strictly unofficial visits. What their job was and how they did it is best told by one of themselves, and Tubby here commends to us the modest and splendid story.

“UNKNOWN WARRIORS”

It is the diary of Sister K.E. Luard, R.R.C., one of the six nurses who made their way to Talbot House in Poperinghe. When I first went to France, I found her at Le Trepot, and had the joy of working with her there. Then she went up the line, and specialised in a peculiar post, as dangerous as it was devoted. She had charge of Advanced Casualty Clearing Stations, set up before each battle area in turn; and for the next three years worked nearer to the line than many men, and saved more lives thereby than any one can reckon. Her hospitals in the Salient were at Brandhoek and at Elverdinghe; and both were shelled and bombed—no doubt by accident; for troops and guns and dumps lay all around them. Yet the risk was worth the running; for the presence of her unit with its marvellous equipment and magnificent team-spirit meant that men who would have died of their wounds on a longer journey, were succoured and saved by immediate operations, conducted on the fringe of the battle itself.

Small mention is made of this in her Diary, though there are glimpses here and there of being “ordered back”, and of winning hesitating consent to the return of herself and her nurses to their forward position, Lord Allenby’s Preface pictures the matter perfectly. The work was indispensable: the danger must be run.

But of the book itself, what can I say which will not mar its meaning? If you would know the truth about these men, here is a witness who disguises nothing. Each page is vibrant with the two great themes—the awful waste of men, the shy splendour that was in them. Here is an eye and pen at work upon the spot: it is no trumped up act of distant recollections. Here is the evidence of a noble and acute mind, put down without rose spectacles. No one can read it without hating war; no one can read it without a deepened reverence for ordinary men. I trust that it will become a landmark in every Toc H library, and a source of inspiration throughout our membership.

….. I despise myself for inserting even italics into Sister Luard’s perfect narrative. The book itself is wholly free from them, and free no less from morbid sentiment, Toc H, for the sake of its own soul, must without more delay, enrich itself with this amazing record, in perfect taste and quiet, delicious English.

TUBBY.

TUBBY CLAYTON

Rev Philip Thomas Byard Clayton, Anglican Clergyman and the founder of Toc H, was born 1885 in Australia to English parents who returned to England when he was two. He was educated at St Paul’s School, London and Exeter College, Oxford, where he gained a 1st in Theology. He died in 1972.

In 1915 he went to France as an Army Chaplain in the First World War. He and Rev. Neville Talbot opened Talbot House, a rest home for soldiers at Poperinghe, Belgium, known as Toc H (being the signal terminology for T.H. or Talbot House) which was a unique place of rest and sanctuary.

Talbot House, Poperinge, Belgium – now a museum

in which Kate Luard is featured

Kate Luard left France on 28 November 1918, resigning from the nursing service so that she could return home to look after her ailing father. Following his death on 28 January 1919, she resumed her role as Matron of the Berks & Bucks County Sanatorium but was clearly restless. Her age, she was by now almost 50, was making it difficult for her to secure a senior hospital position. She was then appointed to the South London Hospital for Women.

Her last position as a nurse was as Lady Matron at BradfieldCollege in Berkshire.

Bradfield College founded 1850; an early photograph

Extracts from the BradfieldCollege obituary and letter from an OB:

At Bradfield she inspired complete confidence in masters and parents alike, though would- be malingerers received short shift but the genuine patient received every sympathy and learned too the full benefit of her great experience and skill. To be brought to her shocked after some accident was to know all the reassurance given by devotion, gentleness and efficiency.

Gradually her back became more troublesome and she retired in December 1930. She then returned to Essex sharing a home “Abbotts” in Wickham Bishops with her two sisters G (Georgina) and Rose.

Abbotts, Wickham Bishops, 1933

Abbotts, Wickham Bishops, 1933

She continued to travel whenever she could and never without her sketchbook. With her brother Percy she toured the battlefields on the Western and Eastern Fronts. With the Canon of St Albans she set up nursing homes for returning troops.

Amongst other activities she was on the committees of both the Anti-Gas Demonstrations 1936 and the Witham Air Raid Precautions 1938.

Air Raid Precaution A.R.P. information WW2

Gradually her back became more troublesome and she had to abandon local activities and the garden which was her joy. She retired from being Commandant of the Essex 24 Women’s Detachment (Witham and Kelvedon) of the British Red Cross Society in 1940 and was made a life vice-president of the BRCS.

In time she became increasingly incapacitated and finally bedridden. To the end she retained a close interest in Bradfield and nothing gave her more pleasure than a letter or visit from someone connected with the school. She also enjoyed the visits and support of her surviving siblings and her nieces, nephews and friends.

She died, aged 90, on 16 August 1962. Her grave and headstone are in St Bartholomew’s churchyard, Wickham Bishops, alongside those of her sisters G and Rose.

Comment from a local historian:

… and there lies KEL, a remarkable person, quietly resting in a country churchyard with some of her siblings, with no great pomp. Quintessentially English to my way of thinking.

Essex Record Office: D/DLu 55/13/1

Kate Luard wrote this soon after the death of her niece Joan on 20th October 1918, aged 19 in the influenza epidemic, who was the daughter of Kate’s brother Frank Luard RMLI, killed at Gallipoli in 1915, and his wife Ellie.

The letter is to her sisters G (Georgina) and N (Nettie) but like her other letters would be passed round to all the family. Rose and Daisy are her youngest sisters.

Sunday night Nov 10th

Dear G & N – you have given me the details about Oxford that I was wanting to know – but Ellie must tell me all the heavenly and funny things Joan said one day. Rose’s letter today of her friend who died the day they found it out shows what a treacherous illness it is: just the same happens to me here – while I am writing to the mother to say he is seriously ill, a slip comes from the Ward to say he is dead. And I don’t think any doctoring or nursing has the slightest effect in this virulent pneumonia. You might as well give an empty cylinder as give oxygen, their lungs get blocked and their lips and faces turn black and it is all over. The delirium is one of the most difficult parts when you are short of staff. I stopped one dying Sergt who was getting out of bed with nothing but a pyjama jacket on, because he wanted to get to his men. “No officers?” he kept saying. “Are there no officers? then I must take charge”

Or they get a fixed idea that they are ‘absent without leave’ and ‘must ‘rejoin my battalion’. None of us have ever seen it before in this virulent epidemic form & the mortality is extraordinarily depressing. In one ward 17 out of 21 died in a few days – Everyone in the influenza wards has to wear a gauze mask & we make a point of off duty time for them – So far only 1 Sister & 2 VADs + three orderlies have gone sick with it and they are not pneumonic, several Sisters & 1 VAD have died at the Sick Sisters Hosp, No.8 Gen.

I think it is abating a little. I am so glad Rose is having a rest. Did G go back to Mr A’s? When does Daisy come back from Nash?

There is the most angelic baby Gerry here who had his leg off yesterday. He is so pleased that his mother will see him with a new leg with no pain in it. He has shining golden hair, blue eyes and a child’s smile. Everyone spoils him. We haven’t nearly so many in now. All our best wards are British again.

About the War, is this really the last night our RA7 will go over dropping destruction into hundreds of Germans? They have already stopped coming over to us I believe. Is tomorrow morning the last time of ‘standing to’, & listening posts, & firesteps, & swimming canals under machine-gun fire & Zero hours & fractured femurs & smashed jaws & mustard gas & the crash of bombs and all the strange doings of the past 4 years?

It is quite impossible for a war-soaked brain like mine to think in terms of peace: war has come to be natural – peace unnatural.

This afternoon at the lovely big service at the cathedral – just like St Paul’s, with beautiful singing – & the sun lighting up the tracings of the roof, one realised that all the War intercessions of the last 4 years are about to be answered & as far as actual War goes will be meaningless after tomorrow – though the sick & wounded & bereaved part goes on yet. What a vital act of new Intercessions the Nations will need now, with the warnings of Russia Bulgaria Austria & Germany all disrupting in turn.

There’s nothing Bolshevvy about us or the French thank goodness. The French are so domestic & practical & matter of fact just now. In Rouen, (apart from the British occupation it amounts to that) you’d never know there’d been a War.

I can’t help wishing Foch had asked Douglas Haig as well as his old pal & Rosie [Rosslyn] Wemyss to meet the German Plenies [a German family]. He wouldn’t have won this War without us.

I wish we could ask R W to lunch one day & make him tell us about it – the bowing & saluting & Foch refusing point blank to suspend hostilities during the 72 hours.

What I feel nervous about is who’s going to be responsible for carrying out our terms if they accept them, now they’ve booted out William [Wilhelm 11, Kaiser] & Max [ Maximillian Hoffman], & probably Hindenburg & Tirpitz & Ludendorff & Hertling & Hollweg & everyone who has ever run the ship of state? Can the saddler control the nation?

In a way it seems almost a bigger change from War to Peace than it was from Peace to War, perhaps because there was nothing very glorious about our last ten years of peace and everything about our 4 years of War has been very glorious.

Goodnight, love to Father, KEL

1000 thanks for all your letters

Kate Luard’s brother Frank William Luard RMLI was killed at Gallipoli on 13 July 1915.

October 2018 is the centenary month of the death of his daughter Joan Anstace de Beauregard in the influenza epidemic at the end of WW1 – on 20 October 1918 aged only 19.

Frank Luard killed at Gallipoli July 1915

The Portsmouth Battalion were at Forton Barracks, Gosport, when the decision was made to take the Dardenelles. The battalion marched 60 miles to Blandford where Frank wrote to his father on 18 January 1915: “ I march by road with my 30 officers and 1000 men for Dorsetshire—my men are to be lodged and fed by Dorsetshire villagers—a new departure in English rural life.”

On Saturday 27 February 1915 the battalion was paraded in pouring rain, followed by a two hour march to Shillingstone Station, from where 30 officers and 944 other ranks were transported to Avonmouth to board the GloucesterCastle—setting sail on 28 February for the Greek island of Lemnos, arriving there on 11 March. They anchored off Gaba Tepe where they witnessed the shelling of 19 March. They expected to land but instead sailed back to Lemnos where they were diverted to Alexandria. After further problems the battalion landed at Port Said, leaving Port Said on 9 April for Lemnos but were diverted to Skyros. On 28 April 1915 the Portsmouth Battalion was ordered to disembark at Anzac Cove to take over No.2 Section of the defences held by the Australian and New Zealand forces at the Western edge of Lone Pine plateau. The Portsmouth Battalion led by Colonel Luard came under immediate attack. Ordered to relieve the Chatham battalion at Pope’s Hill they came under continuous machine gun fire; and at this point Colonel Luard was hit in the right leg. The cost to the battalion over these initial few days was heavy, ten officers killed and seven wounded, with 98 other ranks killed, 305 wounded and 28 missing.

Back in Gallipoli after having been treated in Alexandria for the wound he had received two months earlier, he wrote to his family in a letter dated July 11th 1915 saying: “We did not go back to the trenches as expected … the men however don’t get much rest as we are digging new communication trenches … We lose a man or two each day as the enemy are shelling where they think we are working … The middle of the day is very hot—too hot for sleep—and pervaded with myriads of flies which cover your food, face and hands. We are in a good deal of trouble with diarrhoea—one part of the treatment is brandy and port …”

Two days after writing this letter Frank was killed in action. According to the official records he ‘died most gallantly at the head of his battalion whilst leading his men’. His grave remains in Gallipoli, his widow Ellie having said: “I wouldn’t take Frank’s body from the field of glory for anything—what could be finer than to lie there where his work was done that day.”

BATTLE OF AMIENS August 1918

In 1918 the Allies launched a series of attacks on the Western Front known as the Hundred Days War, 8 August-11 November 1918, which was the final campaign beginning with the Battle of Amiens and ending with the Armistice.

Kate Luard re-joins No.41 Casualty Clearing Station at Pernois, between Amiens and Doullens on 9 May 1918. Here the casualty clearing station, on a new site, is prepared for the Allied Offensive.

Officers’ ward at the 41st Casualty Clearing Station 1918

Officers’ ward at the 41st Casualty Clearing Station 1918

Tuesday, August 6th. For a week past the air has been thick with rumours of a Giant Push, of Divisions going back into the Line after only 24 hours out, of 1,000 Tanks massing in front of us, Cavalry pushing up, and for 5 nights running we heard troops passing through our village in the valley below to the number of 40,000. To-day two trains cleared us of all but the few unfit for travel, and to-night we have got the Hospital mobilised for Zero and every man to his station. As the 1st Cavalry Division was trotting by in the dark, the men calling cheerily, ‘Keep an empty bed for me’ or ‘We’re going to Berlin this time’.

Wednesday, August 7th. 11 p.m. Brilliant sun to-day, after the heavy rains for weeks past. We’ve had a long day of renewed preparations.

All is ready for Berlin. I’m hoping breathlessly that they hold back my leave to see this through.

Thursday, August 8th, or rather 4 a.m. August 9th. 20,000 prisoners, 20 kilometres, 200 guns, transport captured, bombs continually on the congested fleeing armies – and here on our side the men who’ve made this happen, and given their eyes, limbs, jaws and lives in doing so. It is an extraordinary jumble of a bigger feeling of Victory and the wicked piteous sacrifice of all these men.

I have 34 Sisters and the place is crawling with Surgeons but we want more stretcher bearers.

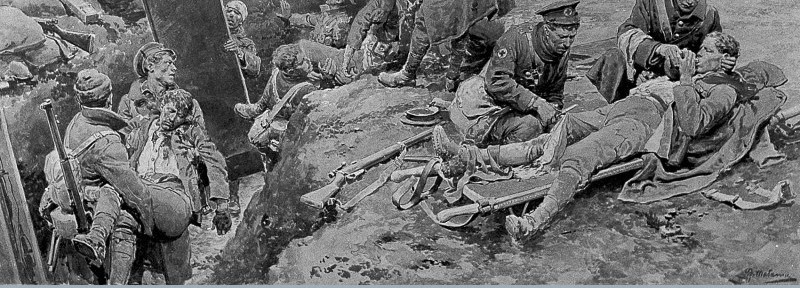

Wounded on Stretchers: Battle of Amiens 8 August 1918

Wounded on Stretchers: Battle of Amiens 8 August 1918

Saturday, August 10th, 10 p.m. By now we [the Allies] should be in Marchelepot again. It is fine to hear of our bridges at Péronne and Brie, that we knew and saw being built by Sappers, being bombed before he [the Germans]can get back over them. (The sky at the moment is like Piccadilly Circus, with our squadrons going over for their night’s work.) The wounded, nearly all machine- gun bullets – very few shell wounds, as his guns are busy running away: very few walking wounded have come down compared to the last Battle – in fifties rather than hundreds at a time, but we have a lot of stretcher-cases. Of course we are all up to our necks in dealing with them, with ten Teams.

There are great stories of a 15-inch gun mounted on a Railway, with two trains full of ammunition being taken. … We have a great many German wounded. For some never-failing reason the Orderlies and the men fall over each other trying to make the Jerries comfortable.

German prisoners arriving at a POW camp near Amiens: 9 August 1918

Must go round the Hospital now and then to bed. The Colonel tells me that nothing has come through yet, thank goodness, about my leave. He says he has written a letter to our H.Q. that would melt a heart of stone.

August 11th. Orders have come for me to ‘proceed forthwith’ to Boulogne for leave. That probably means that I shall not rejoin this Unit.

For Kate’s description of setting up No.41 Casualty Clearing Station in anticipation of the Allied advance – scroll down to see blog: THE ALLIED ADVANCE below – posted 13 May 1918.

After returning from leave all Kate’s letters home are written from two Base Hospitals until her resignation on 28 November 1918 in order to return home to look after her ailing father

Who can use Chavasse VC House Recovery Centre?

Our recovery services at Chavasse VC House are available to all wounded, injured and sick Service Personnel, Veterans and their loved ones.

What is Chavasse VC House Recovery Centre?

Whether returning for duty or transitioning to civilian life, residents and day visitors at Chavasse VC House can take part in activities and life skills courses to help them get back out doing what they enjoy most. The Centre aims to inspire those who have been wounded, injured or become sick while serving our country and enable them to lead active, independent and fulfilling lives.

The Centre has been specially designed to offer the very best recovery atmosphere. It offers 27 single en-suite bedrooms and two family suites. A creative kitchen, presentation room, two lounges, and an adaptive gym with specialist equipment also form part of the Centre. The Hope on the HorizonGarden provides a space to relax and take stock.

The facility also houses a revolutionary Help for Heroes Support Hub which will gives Servicemen, women and Veterans access to specialist Service charities and agencies in a single location, ensuring that they are easily able to access the support they need.

The relaxed atmosphere promotes general wellbeing, and residents are encouraged to undertake their own recovery programme under the guidance of specialist staff. It may involve educational courses, work placements, medical appointments or sporting activities. These activities are designed to improve personal independence, raise morale, and develop camaraderie with others who have been injured or become sick.

How do I contact Chavasse VC House Recovery Centre?

Twitter: @ChavasseVCHouse

Chapter 7 THE ALLIED ADVANCE

May 13th to 10th August 1918 with the 4th Army (Sir Henry Rawlinson)

LETTERS FROM PERNOIS

Between May and August 1918 the Germans made no further progress and it was clear the German army was overstretched and weakened from their Spring Offensive; the Allies launched a counter attack in the summer of 1918. The Germans at Amiens had not had the time to build up their defences and the British Expeditionary Force’s combined artillery, infantry and tank offensive, with the French Army as well as troops from the United States and Italy, launched an offensive decisively turning the tide of war toward an Allied victory.

The Allied offensive began with the Battle of Amiens on 8 August and continued to 11 November – known as the Hundred Days Offensive.

Kate Luard rejoins No.41 Casualty Clearing Station at Pernois between Amiens and Doullens on 9 May. Here she sometimes has time to write home about the landscape and countryside before the Allied Advance commences.

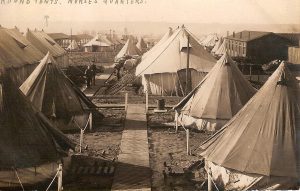

Monday, May 13th. Pernois. There is so much to see to in starting a new site with a new Mess consisting of Nothing, with the patients already in the Wards when we arrived, that there has not been a moment yet to unpack my kit, barely to read my mails, let alone to write letters, other than official and Break-the-News, till now 10.30 p.m.

We had our first rain to-day with the new moon, and the place has been a swamp all day. The great Boche effort is supposed to be imminent and this wet will delay and disgust him.

The C.O. of this Unit is very keen, full of brains, discipline and ideas. Everyone is out for efficiency and we are all working together like honeybees. There is a very fine spirit in the place. The Sisters are all so pleased with our unique Quarters that they’re ready for anything. The C.O. has gone this time to the opposite extreme from daisies under our beds and we are sleeping in the most thrilling dug-outs I’ve ever seen. …………

The Camp itself is very well laid out with roads to the entrances to the wards for Ambulances, to save carrying stretchers a long way. We evacuate by car to the train at the bottom of the valley.

May 22nd, and the hottest day of the year. This full moon is, of course, bringing an epidemic of night bombing at Abbeville, Étaples and all about up here. ……. I had a lovely motor run to the Southern Area B.R.C.S. [British Red Cross Society] Depot yesterday, through shady roads with orchards blazing with buttercups.

May 25th. Nothing to report here: people seem to think he [the Germans] has his tail down too badly to come on, and it looks like it. An inimitable Jock told me to-day that you only had to fill a Scot up wi’ rum and he could do for as many machine-gun nests as any Tank!

May 28th. There’s nothing to say that one may write about, but a good deal to do.

Whit Sunday. We had a divine day here and it’s a translucent night of sunset, stars and moon and aeroplanes, and spoilt by the thunder of the guns which are very busy now on both sides. This is a Sky Thoroughfare between many Aerodromes and the Line, and from sunset onwards the sky is thick with planes, and the humming and droning is incessant and very disturbing for sleep. There are a hundred interesting things one would like to tell you, but everything comes under forbidden headings.

The men have the same spirit, the same detached acceptance of their injuries, and the same blind unquestioning obedience to every order, the same alacrity to give up their pillows ….. as at the beginning of this War. And they are all like that – the Londoners, the Scots, the Counties, the Irish, the Canadians and the Aussies and the New Zealanders.

The Jock is helping in a Ward and bends over a pneumonia man helping him to cough, or cajoling him to take his feeds, with an almost more than maternal tenderness or … helps with a dressing with a gentleness and delicacy that no nurse could hope to beat.

Their obedience is another unfailing quality. When a convoy comes in at night they’re out of bed in a second, filling hot bottles, and undressing new patients and careering round with drinks. If a boy asks for a fag after a bad dressing they literally rush to be first to get him one of theirs.

I could do with some more Sisters. Must do a round now and see what’s likely to be wanted during the night.

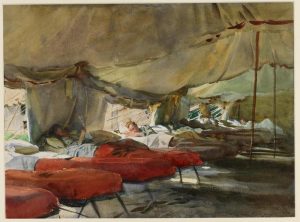

Officers’ Ward at the 41st Casualty Clearing Station 1918 by J Hodgson Lobley

Officers’ Ward at the 41st Casualty Clearing Station 1918 by J Hodgson Lobley

Tuesday, June 4th, 10.30 p.m. He is at this moment making the dickens of an angry noise about 100 feet directly overhead: whether he means to unload here or not remains to be seen. We’ve had rather a busy week …

The weather continues unnaturally radiant. I have never worked in a more lovely spot in this war. There is always a breeze waving over the cornfields and the hills are covered with woods near the valleys, with open downs at the top. Below are streams through shady orchards and rustling poplars – and you can see for miles from the downs.

We had two French girls, sisters of 19 and 16, in, badly gassed and one wounded. I took them to the French Civilian hospital at Abbeville the next day. They were such angels of goodness, blistered by mustard gas literally from head to foot, and breathing badly. They came from near Albert.

Fritz has made a horrid mess of Abbeville since we were there a month ago: 10 W.A.A.C.’s [Women’s Auxiliary Army Corps] were killed at once one day.

Sunday, June 16th. The hills are covered with waving corn, like watered silk in the wind, with deep crimson clover, and with fields of huge oxeye daisies, like moving sheets. To-day there is no sound of guns and it is all Peace and loveliness. All the worst patients are improving and the Colonel has come back from his leave. We are able to get fresh butter, milk from the cow, and eggs, from the farms about and generally fresh vegetables.

Monday, June 17th. Last night he was over us again and working up to his old form: he passed overhead flying very low a good deal, from 11 p.m. The sky illuminations in this wide expanse on these occasions are lovely: searchlights, signals, flares and flashes. We had a busyish night with operations.

June 29th. We are still very busy with influenza [the start of the great influenza epidemic] and also some badly wounded. Jerry comes every night again and drops below the barrage: I think he gets low enough to see our huge Red Cross. Nearly all the wards are dug in about 5 feet and were much approved by the D.M.S. yesterday. There are four badly wounded officers who need a lot of looking after. The problem is to get the influenzas well enough to go back to the Line and yet have room for the new ones.

Allied Advance: British and Belgian wounded 1918

Allied Advance: British and Belgian wounded 1918

Tuesday, August 6th. For a week past the air has been thick with rumours of a Giant Push, of Divisions going back into the Line after only 24 hours out, of 1,000 Tanks massing in front of us, Cavalry pushing up, and for 5 nights running we heard troops passing through our village in the valley below to the number of 40,000. To-day two trains cleared us of all but the few unfit for travel, and to-night we have got the Hospital mobilised for Zero and every man to his station. As the 1st Cavalry Division was trotting by in the dark, the men calling cheerily, ‘Keep an empty bed for me’ or ‘We’re going to Berlin this time’.

Wednesday, August 7th. 11 p.m. Brilliant sun to-day, after the heavy rains for weeks past. We’ve had a long day of renewed preparations.

All is ready for Berlin. I’m hoping breathlessly that they hold back my leave to see this through.

Thursday, August 8th, or rather 4 a.m. August 9th. 20,000 prisoners, 20 kilometres, 200 guns, transport captured, bombs continually on the congested fleeing armies – and here on our side the men who’ve made this happen, and given their eyes,, limbs, jaws and lives in doing so. It is an extraordinary jumble of a bigger feeling of Victory and the wicked piteous sacrifice of all these men.

I have 34 Sisters and the place is crawling with Surgeons but we want more stretcher bearers.

Saturday, August 10th, 10 p.m. By now we [the Allies] should be in Marchelepot again. It is fine to hear of our bridges at Péronne and Brie, that we knew and saw being built by Sappers, being bombed before he [the Germans] can get back over them. (The sky at the moment is like Piccadilly Circus, with our squadrons going over for their night’s work.) The wounded, nearly all machine- gun bullets – very few shell wounds, as his guns are busy running away: very few walking wounded have come down compared to the last Battle – in fifties rather than hundreds at a time, but we have a lot of stretcher-cases. Of course we are all up to our necks in dealing with them, with ten Teams.

There are great stories of a 15-inch gun mounted on a Railway, with two trains full of ammunition being taken. … We have a great many German wounded. For some never-failing reason the Orderlies and the men fall over each other trying to make the Jerries comfortable.

Must go round the Hospital now and then to bed. The Colonel tells me that nothing has come through yet, thank goodness, about my leave. He says he has written a letter to our H.Q. that would melt a heart of stone.

August 11th. Orders have come for me to ‘proceed forthwith’ to Boulogne for leave. That probably means that I shall not rejoin this Unit.

After returning from leave all Kate’s letters home are written from two Base Hospitals until her resignation on 28 November 1918 in order to return home to look after her ailing father.

On the night of 17/18 April 1918 the Germans bombarded the area behind Villers-Bretonneux with mustard gas causing many casualties. Villers-Bretonneux fell to the Germans on 24 April. Kate Luard describes treating the gassed men in her letter of 18 April:

55th Division gas casualties April 1918

April 18th 1918 … the enemy made a great bid for Villers-Bretonneux early yesterday morning, beginning with a terrific drenching with gas shells.

We had over 500 gassed men in and every spot of every floor was covered with them, coughing, spitting & crying with the pain in their eyes. All hands were piped to cope & it went on all night. They have to be stripped as their clothes are soaked with gas and their bodies washed down with chloride of lime, their eyes and mouths swabbed with Bicarb of Soda & drinks & clothing given … You give them jam tins to be sick in and go round with Soda Bicarb in large pails. The worst are in a special ward having continuous oxygen, but some are drowning in their own secretions in spite of it. It is devilish. Two trains are now evacuating all fit to be put on them.

It is pouring with rain, and the ground is a slithering quagmire.

(Kate’s letter home transcribed by Tim Luard at the Essex Record Office)

After the evacuation of all the patients and staff at No.32 Casualty Clearing Station, Kate Luard does a stint as a Railway Transport Officer before taking over as Sister-in-Charge of No.41 CCS at Nampes.

Saturday, Easter Eve, March 30th 1918. Yesterday evening Miss McCarthy turned me into a Railway Transport Officer at the Railway Station, and it is the most absolutely godless job you could have. You must have command of a) the French language, b) your temper, c) any number of Sisters and V.A.D.s, d) every French porter you can threaten or bribe, e) the distracted R.T.O. and his clerks.

No mail has reached me since we cleared out this day week; do write soon to No.2 Stationary Hospital. I am quite fit.

German and British wounded by a British Ambulance train 1918

Easter Monday, April 1st. It has been a dazzling spring day after the heavy rain – spent as usual at the Station – not as R.T.O. this time but as A.M.F.O. (Army Military Forwarding Officer). The day after I last wrote to you, I had a 24 hours’ shift of R.T.O. … puddling about the platforms in the cold and wet. There are no waiting rooms, and the place was a seething mass of refugee families, and French soldiers and my herds of Sisters and kits. But they all got safely landed in their right trains and no kit lost.

Easter Tuesday. Had a very busy day at Triage as A.M.F.O. with my fatigue party fetching and loading kit. And a message came through from Miss McCarthy this evening – was I ready and fit for another C.C.S.? The answer was in the Affirmative.

Wednesday, April 3rd. Letters at last, joy of joys. The Times man is right … and it is all the things he has to leave out of his accounts, the little things officers and men from the Line tell us, that would show you why. And there are weeks of strain ahead …

Saturday night, April 6th. All your letters of the first day of the Battle are coming in. I didn’t quite realise you’d be really worrying. It came so suddenly, and running the wounded and the Sisters gave one no time at all to think – I couldn’t have let you know any sooner. We are plunged in work just now. Every available man has had to be put into the Wards – all the Clerks, Assistant Matron – everyone but the Cook and mess V.A.D.s. I am running two ramping Wards and everyone else is at full stretch. R.T.O. and A.M.F.O. are finished for the time being. All these three Hospitals are understaffed just now and are doing C.C.S. work. We get the men practically straight out of action …

Friday, April 12th. Nampes. Orders came for me on Wednesday to take over this C.C.S. [No.41] at Nampes. It is an absolutely divine spot, south of Amiens. The village is on a winding road, with a heavenly view of hills and woods, which are carpeted with blue violets and periwinkles and cowslips, and starry with anemones. The blue of the French troops in fields and roads adds to the dazzling picture but inside the tents are rows of ‘multiples’ and abdominals, and heads and moribunds, and teams working day and night in the Theatre, to the sound of frequent terrific bombardments. It has never been so incongruously lovely all round.

‘The Interior of a Hospital Tent 1918’ watercolour by John Singer Sargent

‘The Interior of a Hospital Tent 1918’ watercolour by John Singer Sargent

This is the place where four derelict Casualty Clearing Stations amalgamated and got to work during the Retreat, without Sisters. Now it is run as one with a huge collection of Medical Officers and Orderlies and Chaplains from Units out of action, and with odds and ends of saved equipment. It is still very primitive with no huts and no duckboards and only stretchers, with not many actual beds, but it is quite workable.

The patients are evacuated as quickly as possible, and the worst ones remain to be nursed here. Of course, the rows of wooden crosses are growing rather appalling, but some lives are being saved.

We live four in a marquee in a field below the road and have daisies growing under our beds, no tarpaulins or boards. I’ve acquired a tin basin and a foot of board on two petrol tins for a wash-stand and am quite comfortable. Our compound has five marquees. French Gunners stray in and sleep on the grass all round us, and a constant stream of Poilus [French WW1 infantrymen] passes up and down the road. It is very noisy at night. The Cathedral has had two shells in it.

We live on boiled mutton every day twice a day: tea, bacon, bread and margarine in ample quantities does the rest. Our Mess Cookhouse is four props and some strips of canvas; three dixies, boiling over a heap of slack between empty petrol tins, is the Kitchen Range, in the open. We get a grand supply of hot water from two Sawyer boilers under the tree. The French village does our laundry.

Sunday, April 14th. He [the Germans] is at Merville, and what next I wonder? Here we are holding him all right, but each night of uproar one wonders when we’ll next be on the road again. The weather has changed and the dry, sunny valley has become a chilly, windy quagmire. There are no fires anywhere and very little oil for the lamps; it is very difficult to keep the men warm, and the crop of wooden crosses grows daily.

April 22nd. We are on the move again. The patients left to-day and the tents are down this evening. I expect we shall go to Abbeville, while they dig themselves in at the new site North of Amiens. Everything is very quiet here, except occasional violent artillery duels and bomb dropping at night.

Tuesday, 23rd. A month since we up and ran away from Jerry. It is Abbeville, and we are sitting on our kit waiting for transport. I wonder how black it looked in England on Saturday week, when Haig said “We have our backs to the wall” – worse than close to, probably.

In Part 1 Kate Luard re-joins No.32 Casualty Clearing Station and as Sister-in-Charge is responsible for setting this up in a new location in anticipation of the German Offensive.

Friday, March 22nd. A ghastly uproar began yesterday, Thursday morning, March 21st. The guns bellowed and the earth shook. Fritz brought off his Zero like clockwork at 4.20 a.m. and in one second plunged our front line in a deluge of High Explosive, gas and smoke, assisted by a thick fog of white mist. Our gunners were temporarily knocked out by gas but soon recovered and gave them hell, which caught their first infantry rush, but they came on and advanced a mile. We suddenly became a front line C.C. S. and the arrival of the wreckage began, continued and has not ended. We began about 9.30 with our usual 14 Sisters and by midnight we numbered 40 as at Brandhoek. Only two Ambulance Trains have come to evacuate the wounded, and the filling up continues. The C.O. and I stayed up all night and to-day, and we have now got people into the 16-hours-on-and-8-off routine in the Theatre etc. We had 102 gassed men in one ward, but only 4 died. Ten girl chauffeurs drove up in the middle of the night with five Operating teams from the Base.

‘Gassed’ oil painting by John Singer Sargent RA 1918

‘Gassed’ oil painting by John Singer Sargent RA 1918

Friday night, 11 p.m. Just off to bed after 40 hours full steam ahead. Everything and everybody is working at very high pressure and yet it makes little impression on the general ghastliness. This is very near the battle, and gets nearer; there are fires on the skyline and to-night bombs are dropping like apples on the country around. The artillery roar has been terrific to-day. Good-night.

Palm Sunday, March 24th, 9 a.m. Amiens. The night before last after writing to you, things looked a bit hot … and the map was altering every hour for the worse … ours was the place where they broke through and came on with their guns at a great pace. All the hot busy morning wind-up increased, and faces looked graver every hour. The guns came nearer, and soon Field Ambulances were behind us and Archies [anti-aircraft guns] cracking the sky with their noise. We stopped taking in because there were no Field Ambulances, and we stopped operating because it was obvious we must evacuate everybody living or dying, or all be made prisoners if anybody survived the shelling that was approaching. Telephone communication with the D.M.S. was more off than on, and roads were getting blocked for many miles, and the railway also. We had a 1000 patients until a train came in at 9 a.m. and took 300. Every ward was full and there were two lines of stretchers down the central duck-walk; we dressed them, fed them, propped them up, picked out the dying at intervals as the day went on, and waited for orders, trains, cars or lorries or anything that might turn up. At 10 a.m. the Colonel wanted me to get all my 40 Sisters away on the Ambulance Train, but as we had these hundreds of badly wounded, we decided to stay …

At mid-day the Matron-in-Chief turned up in her car from Abbeville and came to look out for her 80 Sisters – 40 with me and 40 at the other C.C.S. A made-up temporary train for wounded was expected, and we were to go on whichever Transport turned up first and scrap all our kit except hand-baggage. … the Resuscitation Ward was of course indescribable and the ward of penetrating chests was packed and dreadful. Some of the others died peacefully in the sun and were taken away and buried immediately.

At about 5 p.m. the Railway Transport Officer of the ruined village produced a train with 50 trucks of the 8 chevaux or 40 hommes pattern, and ran alongside the Camp; not enough of course for the wounded of both Hospitals but enough to make some impression. Never was a dirty old empty truck-train given a more eager welcome or greeted with more profound relief. The 150 walking cases were got into open trucks, and the stretchers quickly handed into the others, with an Orderly, a pail of water, feeders and other necessaries in each. One truck was for us, so I got a supply of morphia and hypodermics to use at the stoppages all down the train. Then orders came from the D.M.S. that Ambulance Cars were coming for us, so the Medical Officers took the morphia and most of our kit. There were 300 stretcher cases left but another train was coming for them. The Sister in charge of the other C.C.S. told me Rothenstein [Official War artist William Rothenstein whom Kate met when they were both sketching Péronne Cathedral] was helping in the Wards like an orderly.

The Boche was 4 miles this side of Ham, just into Péronne, and 3 miles from us – 13 miles nearer in 2½ days. I am glad I have seen Péronne. The 8th Warwicks marched in on March 19th 1917. The Germans will take down our notice board on March 23rd 1918 and put up theirs.

German reserves advancing through St Quentin

German reserves advancing through St Quentin

We got off in 4 Ambulance Cars escorted by three Motor Ambulance Convoy Officers. They had to take us some way round over battlefields and ghastly wrecked woods and villages, as he was shelling the usual road heavily between us and our destination (Amiens). We rook five hours getting there owing to the blocked state of the roads, with Divisions retreating and Divisions reinforcing, French refugees, and big guns being trundled into safety. He chose that evening to bomb Amiens for four hours.

Sunday, March 24th. Amiens. The Stationary Hospital people here were extraordinarily kind and gave us each a stretcher, a blanket and a stretcher-pillow in an empty hut. They had not the remotest idea they would be on the run themselves in a day or two.

Monday, March 25th. 10.30 p.m. Abbeville. It is in Orders that no one may write any details of these few days home yet, so I am keeping this to send home later, but writing it up when I can.

Yesterday afternoon I dug out Colonel Thurston, A.D.M.S. Lines of Communication, and asked him for transport from Amiens to Abbeville. On the Station was a seething mass of British soldiers and French refugees. The Colonel had brought the last 300 stretcher cases down the evening before in open trucks with all the M.O.s [Medical Officers] and personnel. Our wounded were lying in rows along the platform with our Orderlies; they had been in the trucks all night and all day. Some had died; the Padre was burying the others in a field with a sort of running funeral, up to the time they left. They were taken straight to their graves as they died. Now our C.C.S. has no equipment, we shall all, C.O.s, M.O.s, Sisters and men, be used elsewhere.

Wednesday night, 27th. Yesterday I was sent up to No.2 Stationary Hospital to do Assistant Matron by Miss McCarthy [Matron in Chief] and we’ve had a busy day, admitting and evacuating.

On Easter Saturday, March 30th 1918, Kate Luard has a stint as a Railway Transport Officer before moving as Sister-in-Charge to No.41 CCS at Nampes. (See Part 3 to be posted 30 March 2018).

The German advance in the spring of 1918, also known as the Ludendorff Offensive, was a series of German attacks along the Western Front. With Russia now out of the war Germany was able to redeploy troops to the Western Front. It was imperative for the Germans to act before the arrival of American troops. The offensive began on 21 March 1918 and marked the deepest advances by either side since 1914.

On returning from leave Kate Luard spent some months in charge of other units before rejoining No.32 Casualty Clearing Station where once again she was responsible for setting this up in a new location, in anticipation of a German advance.

Chapter 6: The German Advance

Abbeville and Nampes, February 6th to April 6th 1918

With the 5th Army (Sir Hubert Gough)

LETTERS FROM MARCHÉLEPOT

Wednesday, February 6th 1918. Abbeville. Orders came the day before yesterday to report here, and I find it is for my own Unit, at a place behind St Quentin – a line of country quite new to me. None of my old staff are coming but a new brood of chickens awaits me here and I take three up with me to-morrow. In a new Camp after a move there is nothing to eat out of and nothing to sit on, and it’s the dickens starting a Mess and equipping the Wards at once. They sent me all the 60 miles in a car.

Thursday, February 7th. Marchélepot, , south of Péronne. 5th Army. We left Abbeville at 9 p.m. by train to Amiens and got there to find two Ambulances waiting for us. The rest of the run was through open wide country and all the horrors and desolation of the Somme ground, to this place – Marchélepot. There is a grotesque skeleton of a village just behind us, and you fall over barbed wire and in to shell- holes at every step if you walk without light after dark. There is no civil population for miles and miles; it is open grassland – a three years’ tangle of destruction and neglect. All the C.C.S.’s are in miles of desolation behind the lines.

The Colonel and the Officers’ Mess gave us a cheery welcome, and the orderlies are all beaming and looking very fit. I’m thankful that only three Sisters came with me as we found no kitchen, no food, no fire and only some empty Nissen huts, but the Sisters of the C.C.S. alongside have fed and warmed us … sleeping comfortably on our camp beds in one of the Nissen huts and shall have the kitchen started to-morrow. The Hospital has only been dug in since Sunday week – shell holes had to be filled in and grass cut before tents could be pitched or huts put up.

Saturday, February 16th. I expect you’re having about 20 degrees of frost as we are here. Everything in your hut at night, including your own cold body, freezes stiff as iron, but there is a grand sun by day and life is possible again. The patients seem to keep warm enough in the marquees with blankets, hot bottles and hot food, but it is a cold job looking after them.

Fritz has begun his familiar old games. Yesterday he bombed all round, but nothing on us. We are wondering how long our record of no casualties will stand: we are a tempting target, and have no large Red Cross on the ground, and no dug-outs, elephants [small dug-outs reinforced with corrugated iron] or sand bags.

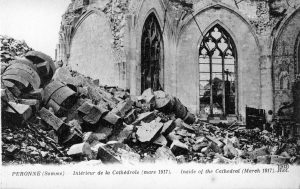

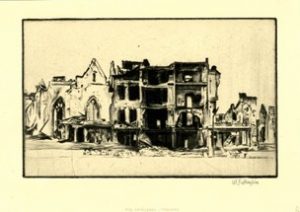

This afternoon I went to Péronne. It was once a beautiful town with a particularly lovely Cathedral Church, white and spacious; only some walls and one row of pillars are left now. It is much more striking seeing a biggish town with its tall houses stripped open from the top floor downwards and the skeleton of the town empty, than even these poor villages, in rubbly heaps.

Destroyed street, Péronne

Sunday, February 17th. Terrific frost still. Drumfire blazing merrily East. I have been trying to draw these ruins. Nothing else of this 15th Century white stone church was visible from where I stood on a heap of bricks. It is quite like it [her sketch], especially the thin tottery bit on the right.  On the other side of my heap of bricks I then found an Official War Office artist [Professor William Rothenstein] drawing it too, and we made friends over the ruins and the War.

On the other side of my heap of bricks I then found an Official War Office artist [Professor William Rothenstein] drawing it too, and we made friends over the ruins and the War.

Ruins and Cathedral, drypoint by Sir William Rothenstein

Monday, February 25th. There is a cold rough gale on to-day, which is a test of our newly pitched Wards and of our tempers. Work is in full swing …. The Colonel knowing my passion for solitude has got me an Armstrong Hut as at Brandhoek and Warlencourt, instead of a quarter Nissen like the rest. It is lined with green canvas and has a wee coal stove and odds and ends of brown linoleum on the floor – all three luxuries I’ve never had before. It looks across the barbed wire and shell-holes straight on to the ruins and the Church.

A terrific bombardment began at 9.30 this evening. We have seen a good deal of Professor Rothenstein. He brought his drawings over to our mess to see.

February 28th. I suppose the newspaper men have long ago got the opening lines of their leaders ready with, “the long expected Battle Wave has rolled up and broken at last, and the Clash of two mighty Armies has begun” etc.etc. It may not be long until they can let it go. Yesterday the C.O.’s of C.C.S.’s of this Army were summoned to a Conference at the D.M.S.’s [Director of Medical Services] Office and given their parts to play. We have arranged accordingly and proceeded in all Departments to indent for Chloroform, Pyjamas, Blankets, Stretchers, Stoves, Hot Water Bottles and what not. The R.E. [Royal Engineers] are working rapidly; Nissen Huts springing up like mushrooms, electric light and water laid on, bath houses concreted, boilers going, duckboards down, and Reinforcements of all ranks arriving. A train is coming to clear the sick to-morrow.

Saturday, March 2nd. Nothing doing so far. Everyone is posted to his right station for Zero and meanwhile the usual routine carries on. To-day there is the most poisonous blizzard. The thin canvas walls of my wee hut are like brown paper in this weather, this violent icy wind blows the roof and walls apart and layers of North Pole and snow come knifing in …

Monday, March 4th. A mighty blizzard snowstorm has covered us and the Boche and there is nothing doing here. Later. the DMS has just been around again with more warnings; and consequently renewed preparations for Zero.

I’ve got some primroses growing in a blue pot, grubbed up out of a ruined garden before the snow. The only way of getting in to my Armstrong Hut at first was across a plank over a shell- hole. The R.E. are fortifying our quarters against bombs. We take in every other day and evacuate about every four days – almost entirely medical cases.

See next post: Friday, March 22nd for start of the offensive on March, 21st

Kate Luard was sister in charge of No.32 Casualty Clearing Station, the most important ‘Advanced Abdominal Centre’ of the war, which also became the most dangerous when her unit was relocated in late July 1917 to Brandhoek to serve the push that was to become the Battle of Passchendaele. Here, alternating with No.44 Casualty Clearing Station and No.3 Australian Casualty Clearing Station, the CCSs were set up to take in the wounded soldiers and operate within hours of their injuries. In her letters home she vividly describes events under the continuous bombardment of shells and guns and the tragic death of Nellie Spindler.

August 22nd, 6 p.m. This has been a very bad day. Big shells coming over about 10 a.m.- one burst between one of our wards and the Sisters’ Quarters of No.44 C.C.S., and killed a night sister asleep in bed in her tent and knocked three others out with concussion and shell-shock.

Thursday, August 23rd. No.10 Sta. St Omer. I’m afraid you’ll be very disappointed, but we are to re-open on the same spot so Leave is off. The Australians are not to go back, but we are to carry on the abdominal work alone as before they came up.

I expected (for one rash day) to be telling you all about this at home to-morrow, but must write it now. The business began about 10 a.m. Two came pretty close after each other and both just cleared us and No.44. The third crashed between Sister E’s ward in our lines and the Sisters’ Quarters of No.44. Bits came over everywhere, pitching at one’s feet as we rushed to the scene of action, and one just missed one of my Night Sisters getting into bed in our Compound. I knew by the crash where it must have gone and found Sister E. as white as a sheet but smiling happily and comforting the terrified patients. Bits tore through her Ward but hurt no one. Having to be thoroughly jovial to the patients on these occasions helps us considerably ourselves. Then I came on to the shell hole and the wrecked tents in the Sisters’ Quarters at 44. A group of stricken M.O.s were standing about and in one tent the Sister was dying. The piece went through her from back to front near her heart. She was only conscious a few minutes and only lived 20 minutes. The Sister who should have been in the tent which was nearest was out for a walk or she would have been blown to bits.

Nellie Spindler QAIMNS from Wakefield was a Staff Nurse at No.44 Casualty Clearing Station and killed in action on 21 August 1917 aged 26. She is buried in Lijssenthoek Military Cemetery, West-Vlaanderen, Belgium.

Tented nurses’ quarters at a casualty clearing station

Wednesday, August 8th. The D.M.S. came to-day and told us to expect work to-morrow but the Satanic Power that presides over the weather in the War has decreed otherwise. Floods of rain dissolving the ground and a violent thunderstorm this evening must have put the lid on any sort of Attack for us. Three men in the Dressing Hut were struck by lightening to-night … Officers from the line tell the grimmest tales. The conditions are appalling; the men are drowning in shell-holes and the enemy artillery are so ‘active’ that the dead are heaping up.

Men jacking up a field gun in an attempt to extract it from the mud

Men jacking up a field gun in an attempt to extract it from the mud

Thursday, August 9th. There is a cheery little Military Decauville Railway for ammunition only – a series of baby trains puff through loaded to the teeth with shells, or coming back with empty cases. Now No.44 C.C.S. is coming in we are no longer the one and only; we can take in alternate 50’s of abdomens and compound fractured femurs.

Friday, August 10th. The attack began on the two corners of the Salient to-day. A lot of abdominals and some femurs are still coming in. Some have died to-day and are dying to-night. …. but we have had an Evacuation by Train this afternoon. A bashed-to-pieces Officer with both legs, both arms, face and back wounded, gassed and nearly blind doesn’t look as if he’d do. (Died at 8 a.m.)

Saturday, August 11th. There is a thunderstorm on and it’s pouring cats and dogs upon our Army

Monday, August 13th. Our 12 Australian Sisters and 10 Australian Orderlies rejoin their own Unit to-morrow. They open to-morrow and we three C.C.S.’s take in now in batches of 50 each, abdomens, chests and femurs.

Tuesday, 14th. Lots of rain and thunderstorms again. Had a run of bad cases to-day, most of whom have died.

Wednesday, August 15th, 11.30 p.m. This has been a horrid day. He bombed a lot of men near by and all who weren’t killed came to us. Some are still alive but about half died here.

7 a.m., Thursday, August 16th. Bombardment still going at top speed. The stream of little trains of H.E. [high explosive] shell passing through the last few days has not been for nothing.

12.30 midnight. There was no sleep after the Blast began last night and we’ve had a mighty day to-day. I feel dazed with going round the rows of silent or groaning wrecks. Many die and their beds are filled instantly. One has got so used to their dying that it conveys no impression beyond a vague sense of medical failure. It is all very like a battle field. He [Fritz] dropped bombs on the Field Ambulance alongside of us, and killed an orderly and wounded others, also on the Officers’ Mess of the Australian C.C.S. alongside of them – not three minutes from us, and killed a Medical Officer and a Corporal.

Saturday, August 18th. Fritz went to C.C.S.’s behind us. At one he wounded three Sisters and blew their cook-boy to pieces. At the other he wounded six Medical Officers among other casualties. A dirty trick, because he has maps and knows which are hospitals back there. Here we are in a continuous line of camps, batteries, dumps, etc.

We have been taking in to-day but not so fast. The letters to relatives who have died-of-wounds are just reaching 400 in less than three weeks. Entering them into one’s book alone is more than one can make time for, but I do write to about a dozen every day or night.

We’ve had two dazzling days, but there is not a blade of grass or a leaf in the Camp.

August 22nd, 6 p.m. This has been a very bad day. Big shells coming over about 10 a.m. – one burst between one of our wards and the Sisters’ Quarters of No.44 C.C.S. and killed a Night Sister asleep in her tent and knocked out three others with concussion and shell shock. This went on all day. The Australians’ Q.M. Stores, the Cemetery, the Field Ambulance alongside, the Church Army Hut, all got hit.

Saturday, August 25th, 10.30 p.m. Brandhoek. Got back here at 8 p.m. [from St Omer] … found everything very quiet, and all our quarters sandbagged to the teeth. The bell-tents are raised and lined inside waist-high with sandbags and our Armstrong Huts outside.

Monday, August 27th. The rain began last evening and is still going on; an inch fell in 8 hours during the night. The ground is already absolutely waterlogged – every little trench inches deep, shell-holes and every attempt at bigger trenches feet deep. And thousands of men are waiting in the positions and will drown if they lie down to sleep.

Three of the men we have in will die to-night, and there’s a brave Jock boy who’s had a leg off and is to lose an arm and an eye to-morrow who said, ‘If you write to Mother, make it as gentle as you can, as she lost my brother in April, died o’wounds’.

Australian troops, Château Wood, Belgium, October 1917

Australian troops, Château Wood, Belgium, October 1917

Sunday, September 2nd. The weather has not cleared up enough yet for Active Operations. Last night some rather nasty shelling was going on and had been all day … and lots of casualties were brought in; 6 died here, besides the killed in the Camps.

Monday, September 3rd. Crowds of letters from mothers and wives who’ve only just heard from the W.O. [War Office] and had no letter from me, are pouring in, and have to be answered. I’ve managed to write 200 so far, but there are 466.

2.30 a.m. … the bomb fell and blew one of our Night Orderlies’ sleeping tents out of existence. They’d all have been wiped out if they’d been in bed, but they were all on Night Duty.

Tuesday morning, September 4th. Got to bed in my clothes, at 4 a.m., up at 7.30. Brilliant morning; Archie racket in full blast. This acre of front so far bears a charmed life, but how long can this last? Shells and bombs shave us on all sides.

Later. Orders have come for the final evacuation of the Hospital – site considered too ‘unhealthy’. We close down to-day, evacuate the patients still here, and disperse the personnel. I stay till the last patient is fit to be moved, probably to-morrow, or next day – then probably Leave for 14 days! But don’t count on it, as you never know.

On returning from leave Kate Luard was sister in charge of No.37 CCS at Godeswaervelde and then No.54 CCS at Merville before rejoining No.32 CCS at Marchelepot with the 5th Army under Sir Hubert Gough, several weeks before the German Advance.

Encouraged by the success of the attack on Messines Ridge in June 1917 General Sir Douglas Haig, who had long awaited a British offensive in Flanders, wanted to reach the Belgian coast to destroy the German submarine bases there. The infantry attack began on 31 July 1917. Constant shelling had churned the clay soil and smashed the drainage systems on the reclaimed marshland. Shortly after this the heaviest rains in more than 30 years began to fall on Flanders.

On 6 November 1917 British and Canadian forces took control of the small village of Passchendaele the name by which the final stages of the Battle of Ypres is known. In 3 ½ months of the offensive the British and Empire forces had advanced barely 5 miles. The British lost an estimated 250,000 casualties including 36,000 Australians, 3,500 New Zealanders and 16,000 Canadians; the Germans 220,000.

UNKNOWN WARRIORS by KATE LUARD

THIRD BATTLE OF YPRES

July 23rd to September 4th 1917 with the 5th Army (Sir Hubert Gough)

LETTERS FROM BRANDHOEK

Kate Luard was Sister in Charge of the most important ‘Advanced Abdominal Centre’ of the war – which also became the most dangerous when her unit was relocated in late July 1917 to Brandhoek and where she had a staff of forty nurses and almost 100 nursing orderlies.

July 23rd. St Omer. Orders came yesterday for us to move and we are just off.

July 25th. Brandhoek. We got to Railhead (Poperinghe) about 5 p.m. The station was being shelled. Everyone was turned out of the train about 1½ miles before the station … and at last the D.M.S. [Director of Medical Services] sent five Ambulances. . …. but here we are. Ten other Sisters had arrived to-day, which makes twenty, and six more come to-morrow. I shall probably have 30. There are about 30 Medical Officers, including some of the pick of the B.E.F. [British Expeditionary Force]; we are for Abdomens and Chests – 8 Theatre Teams.

It is a brilliant starlight night and the battle line, four miles away, is blazing with every conceivable firework and the noise is terrific. We’ve been dished out with gas helmets and tin hats.

Friday July 27th. Yesterday everything went so well one knew it couldn’t last. The hospital had only been pitched since last Saturday and it was really splendid. This venture so close to the Line is of nature an experiment in life-saving, to reduce the mortality rate from abdominal and chest wounds. Hence this Advanced Abdominal Centre, to which all abdominal and chest wounds are taken from a large attacking area, instead of going on with the rest to the C.C.S.’s six miles back.

We are entirely under Canvas, with huge marquees for Wards, except the Theatre which is a long hut. The Wards are both sides of a long, wide central walk of duckboards.

Sir Anthony Bowlby turned up later [Consulting Surgeon to the 2nd Army and Advisor on Surgery to the British Army]. It is his pet scheme getting operations done up here within an hour or two of getting hit, instead of further back or at the Base. That is why our 30 Medical Officers include the largest collection of F.R.C.S.’s ever collected at any Hospital in France before, at Base or Front, twelve operating Surgeons with Theatre Teams working on eight tables continuously for the 24 hours, with 16 hours on and 8 off.

Monday, July 30th, midnight, Brandhoek … By 6 a.m. our part will have begun and everything is organised and ready up to the brim. That we have 15 Theatre Sisters tells its own tale. We have 33 sisters altogether, and they are all tucked into their bell-tents with hankies tied on to the ropes of the first ones to be called when the first case comes in.

Tented nurses’ quarters at a casualty clearing station

Tented nurses’ quarters at a casualty clearing station

We have had a Gas Drill to-night. It is a beastly job and rather complicated, and has to be done in six seconds to be any good; we all take about six minutes! Some Grandmothers (15-inch guns) on each side of us are splitting the air and rocking the huts. Fritz is sending his over too. The illumination is brighter than any lightening: dazzling and beautiful. Their new blinding gas is known as mustard-oil gas; it burns your eyes – sounds jolly doesn’t it? and comes over in shells.

4.15 a.m. The All-together began at 5 minutes to 4. We crept out on the duck boards and saw. It was more wonderful and stupendous than horrible. There was the glare before day-light of the searchlights, star shells and gun- flashes, and the cracking, splitting and thundering of the guns of all calibres at once. No mines have gone up yet.

6.30 a.m. We have just begun taking in our first cases. The mines have been going off since 5 like earthquakes. Lots of high explosive has been coming over, but nothing so far into this Camp. I am going now to the Preparation and Resuscitation Hut.

July 31st, 11 p.m. Everything has been going at full pitch – with the 12 Teams in Theatre only breaking off for hasty meals – the Dressing Hut, the Preparation Ward and Resuscitation and the four huge Acute Wards, which fill up from the Theatre; the Officers’ Ward, the Moribund and German Ward. Soon after 10 o’clock this morning he [Fritz] began putting over high explosives. Everyone had to put on tin hats and carry on. They burst on two sides of us, not 50 yards away – no direct hits on to us but streams of hot shrapnel. …. they came over everywhere, even through our Canvas Huts in our quarters. Luckily we were so frantically busy. It doesn’t look as if we should ever sleep again. Of course, a good many die, but a great many seem to be going to do. We get them one hour after injury, which is our ‘raison d’être’ for being here. . It is pouring rain, alas, and they are brought in sopping.

(Australian casualty clearing station)